Wolfram's theory of everything is interesting, profitable, and probably wrong.

Stephen Wolfram just presented a new fundamental theory for how the universe works that claims to unite quantum mechanics and general relativity. Here are a few highlights:

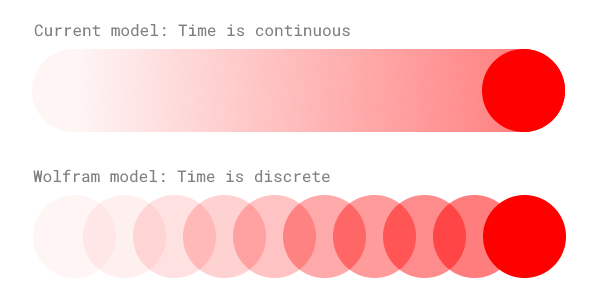

- Time takes place in discrete steps, like the frames of a movie.

- Quantum mechanics and general relativity are both caused by the same thing.

- The number of spacial dimensions can change over time, and doesn’t have to be an integer.

Wolfram’s original article does a good job of explaining the theory quite simply, but it’s still worth summarizing these ideas briefly.

Time takes place in discrete steps.

This one is awesome. Anyone who has edited a video or coded a video game knows that action takes place in a set of discrete “frames”, one right after another. Under wolfram’s proposed theory, the universe works the same way. There is a process that takes the state of the universe at one moment in time and transforms it into the next. Repeating this process generates a series of snapshots of the universe at each moment in time. Unlike existing models of physics, there is no “in between”. If a ball travels from x=1 to x=2, there is no guarantee that it will ever hit exactly x=√2.

This is a very comforting concept. In the universe, big things and small things look mostly the same. The force of gravity pulling together two atoms in a vacuum looks the same as the force between two planets. The scale changes, but the structure doesn’t. Interestingly, this theory of the universe looks a lot like the inside of a computer, and computers often serve as mini universes of their own. If our mini universes match the big universe, that seems to fit with the fractal-like nature of everything.

Quantum mechanics and general relativity are the same.

Speaking of small and large things, Wolfram’s theory combines two seemingly contradictory theories about the way that little and big things behave. The theory states that relativity and the observer effect are both caused by what has been named “causal invariance”.

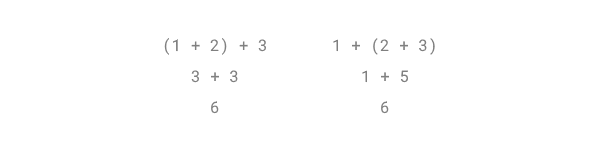

Causal invariance begins with the idea that when the universe takes a “step”, there are sometimes multiple options for what it can do. This is analogous to the adding three numbers. You can begin by adding the first two or by adding the second two. Ultimately, however, you will converge on the same answer no matter which path you choose.

In Wolfram’s proposed model of the universe, all possible variations take place simultaneously. Eventually, however, these branches (almost) always reconvene on the same answer.

These splices and re-convenings of the universe are the foundation of Wolfram’s explanation for both relativity and the observer effect. The idea in both cases is that two observers can see the world differently, but yet they will eventually agree.

Dimensions are flexible.

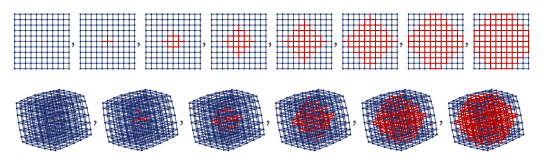

The Wolfram model proposes that “space” and “stuff” are the same, both made up of nodes in one big network. In this abstract arena, measuring dimensionality is a bit tricky.

First, consider a cool property of differently-dimensioned shapes: The area of a 2D circle is proportional to r2, but the volume of a 3D sphere is proportional to r3. The rate of size increase depends on the number of dimensions.

In a network, dimensionality can be measured by applying this fact in reverse. Start at a single node, then expand out to select all connected nodes. Then expand again to select all the next connected nodes. After repeating this process n times, how many nodes are selected? If the answer is proportional to n2, then the network is 2D. If it’s proportional to n3, the network is 3D. Here’s the illustration provided by Wolfram himself:

Of course, in a network like this, dimensionality is just a rough approximation, with two unintuitive properties:

- Dimensionality doesn’t have to be an integer! A 1.5D network is completely valid.

- Dimensionality doesn’t need to be uniform throughout the network. As you move through space, the number of dimensions can change.

Is this marketing?

Absolutely! All throughout the announcement of his theory, Stephen references the Wolfram Language and uses it to generate diagrams of networks. There’s even an entire section dedicated to programming language design which flaunts Wolfram Language and its ability to simulate this model of the universe.

That’s okay. Elon Musk has demonstrated that pursuing financially viable scientific exploration is a great way to make rapid advancements. Financially sustainable research is better than science which requires donations to stay afloat. Making money allows the science to sustain itself, and focuses efforts on making advancements which benefit society.

Is this correct?

If you’re trying to predict whether a “theory of everything” is correct, you’d be hard-pressed to find a better algorithm than to always say “no”. This theory is almost certainly wrong, but that doesn’t mean it should be shunned. Attempting to understand the universe is a valid, virtuous choice. Being wrong is okay. Earning a profit is okay. The only true failure is to never try.